7-second speed read:

- Robots already exist in HR

- Robots can write your CV for you

- Only humans can convince other humans that a pilot job is cool

- HR will focus on high-touch tasks

I recently acquired an iRobot vacuum cleaner to substitute me in house-cleaning. It buys me time to write articles here.

While I may be a late adopter in practice, automata creeps more and more into my prattle on airline operations. That seems to spur from human ingenuity finding applications for robotic process automation away from obvious OCC work, the most recent example being human resources.

Robots are already searching for candidates and interviewing applicants with a recorded video for the human to review. 93% of employees would take direct managerial commands from a non-human manager. So, there’s no obvious reason cost reduction will not further their introduction in human resource management, and more importantly, why the humans shouldn’t already figure out what to skills to specialise in once the androids are a daily part of it.

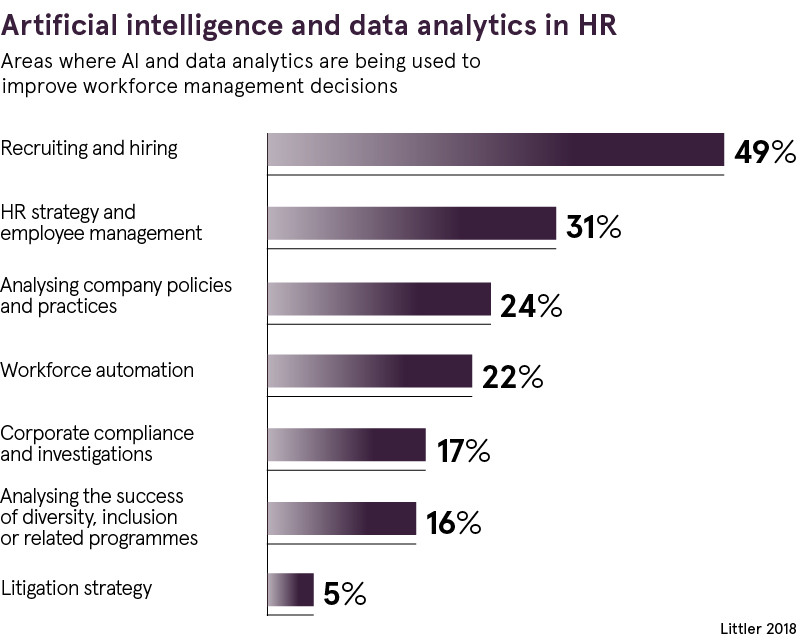

What’s the robot going to be doing in people supervision in the next 5-6 years? What it’s good at: collecting, sorting, and storing data. It will seek the attributes a human decision maker needs (flight hours, valid ratings, medical validity and so on), reducing the candidate to a variable. Considering existing applications in maintenance, it would then not be far-fetched to suggest that by 2025 these same collectors will not only describe who’s applying but also suggest what to do with them (prescriptive analytics) or contact them again based on a forecast of fulfilling requirements at a future date (predictive analysis).

[Perhaps, you will be able to hire one to build your CV? If recruiter robots seek a set of parameters, there’s no reason why a counterpart automated service can’t generate data in a format acceptable to them. A simple chat bot can ask you questions to create a document that you can submit, so you don’t have to (if anyone monetizes this, please acknowledge that you heard it here first!)]

Furthermore, if an HR specialist spends 65% of their time on automatable rule-based processing, they will have to earn their worth otherwise. The AI will still need supervision, so let’s assume only half of the human’s time will be freed up, likely in the application of “soft skills“.

Source: Readers Digest

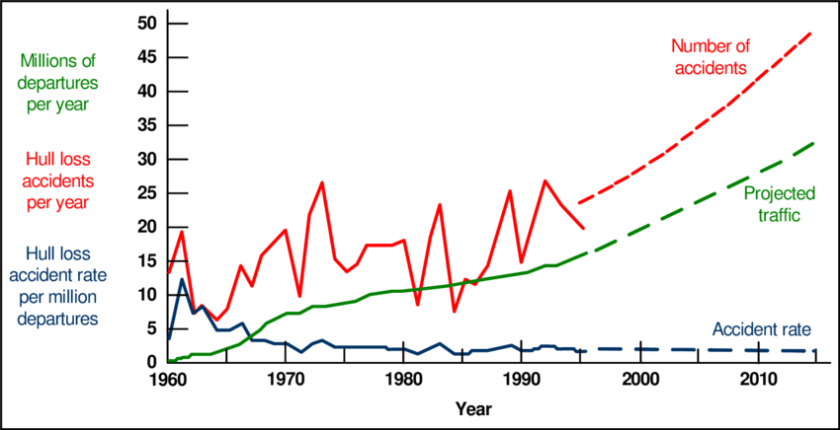

Android lack of these is the butt of many sci-fi jokes (see StarTrek’s Data for more) but witticisms haven’t generated corporate profit yet. HR processes have and humans will need to continue creating employee journey maps. In the pre-employment phase, no robot can reach out to schools and convince pupils that the pilot job is cool. Interviews (“Know me, like me, trust me“) will likely still involve hominid interaction and a “high touch” to assist the high tech.

Later on, during the course of one’s career, management will likely be a mixed bag of algorithm and meat intellect but conflict resolution and motivation talks should remain a spur of a mortal’s emotional intelligence. New roles for employees may be suggested by digital assistant analysis but involving a pilot in tasks not fitting their primary occupation will still need creativity that machines have not demonstrated.

Perhaps some of us will be involved in automating ourselves out of a job and into retirement. At least until now, this path has not been a zero-sum game, leaving undiscovered opportunities to claim.

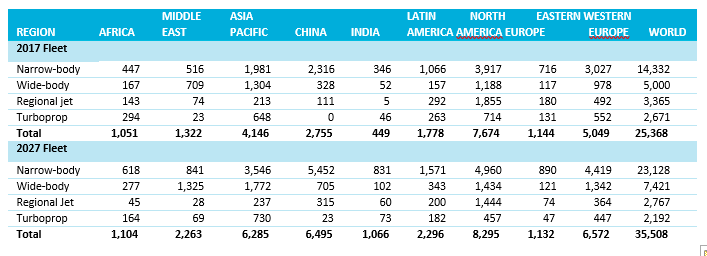

Source:

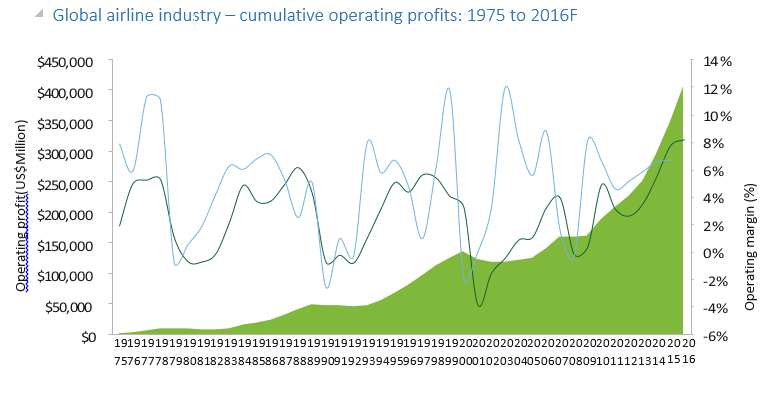

Source:

Airplanes streaming

Airplanes streaming